2018.02.12

“Children in Fukushima are all right” – Message from Thyroid Examination Sites

So far, statements which claim “many Fukushima children are developing thyroid cancer because of radioactive materials released by the accident at the Tokyo Electric Power Company’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station” have repeatedly emerged and circulated via mass media and the internet. In contrast, the mid-term report for fiscal year 2016 of the Fukushima Health Management Survey Oversight Committee (Note 1) and reports from international organizations, including the United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR) 2013 report and its subsequent White Papers (three papers by 2017), present “radiation from the Fukushima nuclear accident is unlikely to increase thyroid cancer among children” (See: “Deliberation on the Debates over Thyroid Cancer in Fukushima – To Protect Fukushima’s Children” [in Japanese])

Note 1: The mid-term report based on the data from the Fukushima Health Management Survey (The Oversight Committee for the Fukushima Health Management Survey, March 2017). Their view remains the same with newer data.

I organized an interviewed between Dr. Ryugo Hayano (Professor Emeritus, the University of Tokyo) who has been actively involved with Fukushima as a scientist in the aftermath of the accident and Dr. Sanae Midorikawa (Associate Professor, Fukushima Medical University) on the past and future of the thyroid examination program in Fukushima. Dr. Midorikawa is a physician who has been contributing to the program since it started in October 2011 (The interview took place in July 2017 and this article was developed in December in the same year.)

Introduction

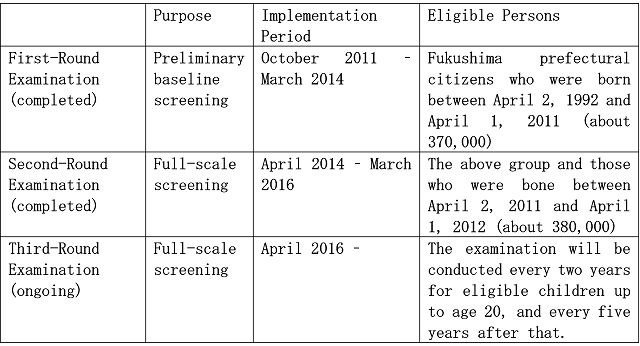

In October 2011 Fukushima Prefecture started thyroid examination after the Fukushima nuclear power plant accident as part of the Fukushima Health Management Survey for approximately 380,000 residents who were aged 18 or under and those who were born in 2011. The examination is intended for children who do not have any symptoms or signs of thyroid cancer, in order words, for those who do not suffer from illness. The main objectives of the examination were “to remove anxieties of Fukushima residents” and “to monitor residents’ physical and mental health.”

After the 1986 accident at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, thousands of children have been diagnosed with “thyroid cancer” and undergone surgery. Physicians from different countries, including Japan, went there and provided medical examination and treatment, and the news of a sharp increase in the incidence of thyroid cancer among children following the Chernobyl accident was reported sensationally around the world. Many Japanese people remembered and clearly recalled the serious consequence of the Chernobyl accident, and they were greatly concerned about children‘s health after the Fukushima accident. Responding to public requests, Fukushima prefecture launched the thyroid examination program.

The program was committed to Fukushima Medical University. The university is equipped with high-level medical facilities and advanced skills, and implements the program under strict protocols to protect personal data. Probably people with strong concerns about radiation would have sought and taken thyroid examination individually at various facilities if Fukushima Prefecture had not officially started the program. Since there were not enough physicians specialized in thyroid, a sudden influx of thyroid examination requests could have led to unreliable examinations and treatments, as well as inadequate protection of children’s personal data.

There was no choice but to start the thyroid examination program.

Hayano: Do you remember where you were and what you were doing on March 11, 2011?

Midorikawa: I was participating in an annual meeting of the Japanese Society for Hypothalamic and Pituitary Tumors in Akihabara, Tokyo. Transportation systems were disrupted considerably by the Great East Japan Earthquake, and thus it was impossible to return immediately to Fukushima. I was afraid I would not see my children again, but fortunately, I somehow managed to go back home although it took me about 24 hours.

After returning to Fukushima, I was worried for a while that the nuclear accident would affect us and wondering what would happen next. As a mother living in the prefecture, I had some ambiguous concerns that the same thing as the Chernobyl might occur if Fukushima children had exposed to high amounts of radiation. Therefore, when I was requested to help the thyroid examination program, I thought that I must do it.

At that time, the role of which I was asked was “to use a probe (a medical instrument of a diagnostic ultrasound system).” There was a severe shortage of physicians who had knowledge and skills to use the device.

In the beginning, thyroid ultrasound examinations were implemented at public facilities, and there were only six ultrasound machines. With the six machines, we examined 500 to 1000 children every day. A great number of people came to the facilities to take the examination day after day. Some people had to wait for a few hours before examination.

Hayano: Given the social circumstances at that time, there was no choice for the prefecture but to start the thyroid examination program. However, in fact, there were no children who were exposed to high levels of radiation during and immediately after the accident. In particular, Iitate Village and Kawamata Town measured about 30 % of registered children (Note 2). Did you already know the data when you got involved in the program?

(Note 2) Kim et al, Internal thyroid doses to Fukushima residents-estimation and issues remaining, J. Radiat. Res. 57 (Suppl 1): i118-i126, 2016

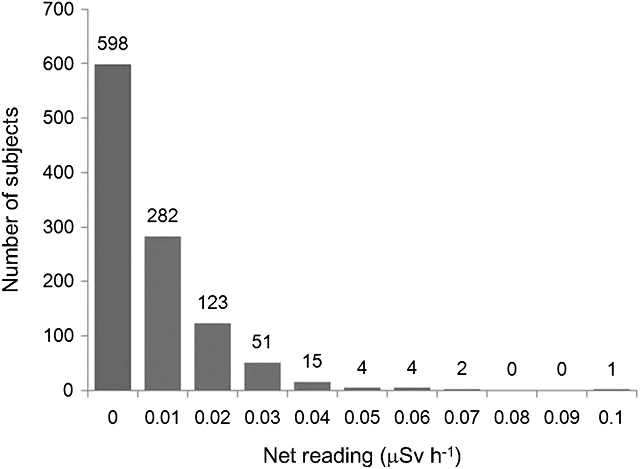

Figure: Data from thyroid dose measurements conducted to 1,080 children from Iitate Village, Kawamata Town and Iwaki City (Kim et al., 2016)

*0.2 μSv/h on the horizontal axis in the figure is equivalent to 100 mSv of thyroid equivalent dose to one-year-old children.

Midorikawa: I learned more about radiation from radiation specialists while performing ultrasound examinations, and I gradually realized that people were not exposed to much radiation. At the same time, this finding raised me a question about the meaning of the screening.

Hayano: I see. You understood that radiation exposure following the accident was limited, and you were asking yourself such question while using a probe.

Midorikawa: The implementation of the thyroid ultrasound examination had already been decided, and many worried residents were bringing their children asking us to examine them. Many children cried loudly when I tried to place a probe on their thyroids. In some cases, I had to hold crying children tightly to do the examination.

I often told mothers “we should not force children to take the examination when they are very afraid and crying. You can take your child outside for a change and help him/her calm down before doing the examination.

But, mothers were desperate and said “No, it doesn’t matter whether my child cries. You can hold him/her down, so please do the examination right now.” This kind of conversation was held every day. And I questioned more strongly whether it was really necessary to have Fukushima children go through such terrifying experience.

Why do we need to perform thyroid examinations?

The first round of screening conducted between October 2011 and March 2014 is called “Preliminary Baseline Thyroid Screening.” In consideration of the fact that it took some years until the incidence of thyroid cancer increased after the Chernobyl accident, the data collected from this screening are viewed as baseline data assuming there were no health effects related to the Fukushima nuclear accident and subsequent radiation exposure. The second-round screening (the second-time examination for participants) and onwards are called “Full-Scale Thyroid Screening.”

The thyroid examination program as part of the Fukushima Health Management Survey is expected to reduce public concerns about radiation and evaluate the effects of the accident-related radiation exposure on thyroid glands based on the comparison of the data from Preliminary Baseline Thyroid Screening and the data from the Full-Scale Thyroid Screening.

Midorikawa: It is very important that we can state “thyroids of Fukushima children do not show any harmful effects of radiation” with scientific evidence. At the same time, clinicians, including myself, are facing patients on a day-to-day basis. Even with the thyroid examination, it has been my role to directly interact with children and mothers at sites and reduce their excess psychological stress about the examination and its result.

Hayano: It is essential to provide a careful explanation about the examination and its result in order to reduce excessive concerns. But, in the beginning, you conducted the examination to as many as about 1,000 children every day. It must have been very difficult to do so to every child and every mother.

Midorikawa: Yes, it was very difficult. Moreover, since the results of the primary examination (thyroid ultrasound examination) have to be reviewed and confirmed by thyroid specialists first, we do not provide the results to children and mothers at the venue immediately after the examinations. In addition, the approach would not be harmonized and cause some adverse influence on them if each examiner explains results individually. For these reasons, we have decided not to tell results to children and mothers at the venue immediately after the examination.

However, considering the concerns of children and mothers, it was not easy for me. It was my sincere hope that we could at least explain basic things thoroughly and clearly, such as what exactly the examination is about and how to understand its result.

In 2013, we decided to have explanatory sessions separately, not only talking to children and their caregivers at examination sites. Shortly after the decision, we first organized on-site explanatory meetings inviting mothers.

Children do not know the purpose of the thyroid examination

The results of the primary examination are classified into three groups. Category A is “further examination is not required”, and it has two subcategories: A1 “No nodules/cysts” and A2 “Nodules ≤5.0 mm and/or cysts ≤ 20.0 mm.”

A “cyst” is a bag-like region filled with fluid and it is relatively common. It is reported as an examination finding, but it does not become cancerous. During the stage of child growth and development, it can emerge and disappear frequently, and therefore, the result of the thyroid examination may change based on when children take the examination. In the latter half of 2012, the word “cyst” increased public concern about their health because most laypersons were not familiar with the terminology. There were some misleading information and public confusions.

Those with nodules ≤5.0 mm do not need to undergo the secondary (confirmatory) examination, and they are requested to wait the primary examination of the next round of screening (this means “advanced examination and any medical treatment are not necessary at this point.” Since Fukushima Prefecture provides the screening periodically, it is stated such way”). In addition, cysts may contain cells (so called “having solid components”) are treated as a “nodule” (a lump of thyroid cells). In such cases, however, the size of “cyst” filled with fluid is measured, not the size of the cells. Hence, even if it is diagnosed as A2 or B (Nodules ≥ 5.1 mm and/or Cysts ≥ 20.1 mm), there are, in fact, no problems in many cases.

Hayano: In general, people visit and consult a doctor when they have some kind of illness symptoms, but it is rare for thyroid cancer. Since such large-scale screening had never been implemented to children without symptoms, probably it was difficult to anticipate how many cases would be identified. Maybe some people expected less.

However, the Preliminary Baseline Thyroid Examination revealed a large number of confirmed or suspected thyroid cancer cases. Whenever new data were issued, they were widely reported by mass media, such as newspapers and television. Around that time, what was your major activity?

Midorikawa: There ware around 2,000 children who fell into Category B in the Preliminary Baseline Survey. However, of those, only 5.6% were actually diagnosed with thyroid cancer. In other words, many of the children with B examination result did not have malignant tumors. But, they were coming to the secondary examination believing that they had thyroid cancer.

For example, some elementary school students burst into tears as soon as they came into a consultation room. In a case like that, my job was to take the children outside the consultation room individually to a place where they could calm down and express their anxiety and fear. It was like something that nurses are nowadays doing, which is so called “psychological care” as part of thyroid screening.

Hayano: You discussed the issues of the approach of the thyroid screening in your article published in 2014 in the Japan Medical Journal, and presented at a symposium held at the Fukushima Medical University in March 2016 that Fukushima children do not know the purpose of the screening. Probably it was not easy for you as a clinician who is engaged in the efforts with the prefectural government to voice such concerns. Did they come from your long-time experiences of directly dealing the struggles of children and mothers?

Midorikawa: Yes, the more I spend time with children and mothers, the more I worry about psychological and physical stress of the examination on children. For example, the secondary examination involves blood and urine laboratory examinations besides additional ultrasound examination. When necessary, cytological examination (fine-needle aspiration cytology) is performed. However, cytological examination is normally conducted when patients experience some symptoms or show signs, indicating the need for surgery. Furthermore, the procedure should be carefully implemented based on a thorough evaluation of its benefits and harms.

However, in Fukushima, the medical procedure is performed to asymptomatic persons based on the initial screening results. Importantly, they are children. It must be far more horrifying for them than it is for adults to have a needle go into their necks.

In school class dialogues sessions, children can show their thyroids correctly when I ask them to show me where their thyroids are. However, they cannot answer if I ask them why they take the thyroid examination. Even if I say “Please raise your hand if you know why. I will not ask you to explain it.”, children hardly raise their hands.

Six years has passed since the screening started, but yet children do not know why they are taking it.

“You may not ever notice in your lifetime that you have thyroid cancer.”

Among thyroid cancer types, there are types that remain small and do not develop any symptoms in lifetime. Moreover, a surgery to remove tumors has certain risks. In some cases, based on the sets of practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of thyroid cancer, doctors recommend patients to choose active surveillance (to monitor the tumors with long-term follow-ups, instead of having a surgery).

However, it can impose considerable psychological burden to patients and their families to worry about the cancer in their everyday lives for a long time. It is not unusual that people with thyroid cancer choose active surveillance instead of having a surgery. In November 2017, we discussed in the meeting of a working group of the Oversight Committee for thyroid examination that it is unrealistic to make children who are diagnosed as thyroid cancer choose active surveillance for nearly a half century.

Hayano: How do you usually approach children and mothers? In particular, considering the fact that “Fukushima people are not exposed to a large amount of radiation,” how do you explain when people ask you why many thyroid cancer cases have been identified after the accident?

Midorikawa: In the first place, thyroid cancer can be found from autopsy (examination of people who died from other causes). This shows that many people have thyroid cancer without realizing it. I say to mothers “If we do not undergo the examination, we may never know that we have thyroid cancer.” This is what I tell mothers and sometimes briefly discuss with children although it is not easy.

Hayano: It must be very hard.

Midorikawa: Generally, we can communicate with people about the illness in more detail during an individual counseling. I have already been doing so to mothers when I get an opportunity to have face-to-face conversations with them. Nevertheless, it has been only one year since we started telling this aspect of thyroid cancer to mothers at larger sessions, and since April this year (2017) I have been telling children in explanatory meetings “Thyroid cancer may be found during the thyroid examination. However, you may never know it in your lifetime if the examination is not conducted.”

It is difficult for children to say “no” to a school-based thyroid examination

The incidence of many cancers, not only thyroid cancer, involves various causal factors, such as aging, heredity and lifestyles, similarly with many other cancers. The independent effects of low-dose radiation exposure on the illness development are much smaller than the effects of those factors, and it is difficult to apportion effects from low-dose radiation among various causal factors In particular, the lower doses are, the more difficult it is to evaluate the independent effects of radiation that are often veiled by other factors.

In 2014, Prof. Kenji Shibuya, a professor of public health at the University of Tokyo, said “the current operation of the thyroid examinations shows a need for improvement,” and pointed out problems of the thyroid screening examination program in Fukushima and a possibility that radiation doses among Fukushima children immediately after the accident were not high to influence their health.

The UNSCEAR 2016 white paper states that it also noted that “the likelihood of a large number of radiation-induced thyroid cancers in Fukushima Prefecture — such as after the Chernobyl accident — could be discounted because absorbed doses to the thyroid after the Fukushima accident were substantially lower.”

Furthermore, at the Prefectural Oversight Committee Meeting for FHMS in October 2017, Dr. Gen Suzuki, Director of the International University of Health and Welfare Clinic, presented an interim report of the research project which re-evaluates Fukushima children’s exposure doses just after the accident. This interim report suggested that average initial thyroid doses due to internal exposures (such as iodine-131 which may cause thyroid cancer) were 5–39 mSv for one-year-old children from 13 municipalities around the power plant; the estimated doses were far lower than the initial estimation (47–83 mSv) discussed in the UNSCEAR 2013 report.

Importantly, the current criterion of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) for the use of stable iodide to block internal exposure is “estimated thyroid equivalent doses exceed 50 mSv in the first 7 days of an emergency.”

Hayano: It is known that there were large differences between the Fukushima nuclear accident and the Chernobyl nuclear accident; in the case of Fukushima, internal exposure such as the intake of radioiodine just after the accident was limited, and the amount of radionuclides emitted from the plant was small, and more stringent food monitoring was implemented with immediate ban on foodstuff from Fukushima, such as milk. Thyroid equivalent doses among residents affected by the Chernobyl accident were far higher than those affected by the Fukushima accident. Finally, Dr. Elizabeth Cardis, Head of the Radiation Group at International Agency for Research on Cancer, drew a dose-response line (i.e., a relationship between thyroid cancer incidences and radiation doses), concluding that the exposure to I after the Chernobyl accident increased thyroid cancer in children (note 3).

(Note 3) Risk of Thyroid Cancer After Exposure to 131 I in Childhood, E. Cardis et al., JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute, Volume 97, (2005) Pages 724–732,

However, in case that the amount of radiation to which Fukushima residents were exposed after the accident was sufficiently low, we would not identify effects of radiation even if we continue screening them. Then, why are we doing the examination?

Midorikawa: In any case, we should discuss who really needs this examination.

At present, Fukushima residents aged 18 years or less at the time of the accident (and those were born during FY 2011) are all informed that they are eligible for the thyroid examination. Although a consent form did not include an option of “not participating” at first, which has been changed since FY2016. People, in this case the parents of eligible children, can decide whether to participate in the examination, we should clearly and precisely explain the benefits and harms of the examination to help them make decision.

Hayano: Participation rates are decreasing sharply especially among people who graduated from high school and left the prefecture. What are the reasons for the decline in participation?

Midorikawa: First of all, the high participation rate of the thyroid examination program (approximately 70%–80%) is mainly attributed to the fact that the program for elementary to high school students has been conducted at schools using class time. The consent form for the program provides an option of non-participation. However, it is psychologically difficult for parents to express they do not wish their children to take the thyroid examination at school.

Second, because the examination is conducted using class time, it seems that some children and their families mistakenly think that the participation in the thyroid screening program is mandatory, like periodical electrocardiogram examination and urine examination which are required by the School Health and Safety Act. Due to these reasons, the school-based screening has significantly high participation rates. On the other hand, once they graduate from school, the participation rates drop sharply. For example, the participation rate for those aged 18 years or older is lower than 20%.

Hayano: In other words, 80% of those who do not have the school-based program after graduation do not participate in the examination. This means that those 80% do not have high anxiety to voluntary participate in the examination. Six years has passed after the nuclear accident. Are there any changes in terms of people’s radiation concerns during these six years?

Midorikawa: I see some changes in mothers. When I explain the results of thyroid examination, nowadays many mothers say, “we did not have a lot of radiation exposure.” Contrary, some mothers do not express anxieties for different reasons. For instance, some say, “I do not want to talk about radiation any more. I put my worry in the back of my mind so that I do not need to think about it much.”

Children are observing mothers who no longer talk about radiation and are sensing why; then they also become hesitant to talk about it. They are not necessary to be less worried about radiation based on acquired knowledge on the topic. At the end of my class dialogues, I always ask children to write down their thoughts on the class dialogues and any questions they may have, and usually a certain number of children write “although I cannot ask other people normally, what would happen if there were another explosion at the Fukushima Daiich Nuclear Power Station?” Some others write “will I be discriminated if I go outside Fukushima?”

Explaining the benefits and harms of the examination carefully.

Europe set up the High Level Expert Group (HLEG) on European Low Dose Risk Research in 2008, and launched the Multidisciplinary European Low Dose Initiative (MELODI) as an international and multidisciplinary organization in 2009 with an aim of facilitating researches on low-dose radiation exposure and fostering human resources.

Based on this background, EU started “SHAMISEN project” in 2015 which aims to implement medical and health surveillance of affected populations and risk communication based on the Fukushima Medical University‘s knowledge and experiences and Europe’s knowledge developed through many years of research .

Hayano: The SHAMISEN project has issued some recommendations including “Do not recommend systematic thyroid cancer screening systematic” (to a large population) even if a nuclear disaster occurs. Do these recommendations sound appropriate from the views of the doctors implementing the program in Fukushima?

Midorikawa: I evaluate those recommendations positively. I also agree with the recommendation that a detailed explanation should be provided to participants to enable them to make decisions when the thyroid examination takes place. I value such various opinions and recommendations from international and multidisciplinary organizations, and the recommendations should be adequately utilized for residents’ well-being.

Hayano: I think that the thyroid examination in Fukushima should not be implemented not only for the sake of formality, and I hope it will be implemented in the way that those who really want to participate in the program can take the examination comfortably.

It would be nice if we could have a system to enable residents to take the thyroid examination comfortably at well-equipped facilities whenever they feel concerns about radiation effects on their health. If we could establish such examination system as one general medical service, it would be worth continuing thyroid examination. But, the current system is not like that.

Midorikawa: Considering the way which the examination should be operated, we need to have the system available to assist those who have high anxiety in taking the examination without worries at any time. Furthermore, it is also very important to first provide those who want to participate in the examination with necessary information sufficiently, such as the possibility of overdiagnosis and illness-management options in the case that thyroid cancer is found.

Hayano: Academically, it may be necessary to document the data obtained from such large-scale examination for next generations in some form or another. However, there are people who actually underwent a surgery as a result of the examination even though they did not have any symptoms. For them this is a serious problem which may affect the rest of their lives. How should we approach such people and their families?

Midorikawa: “Recovering from thyroid cancer” is not the same with “not getting thyroid cancer.” Once tumors are removed through a surgery, thyroid cancer is taken out from a body. But, people remember that they used to have thyroid cancer and sometimes the memory can be linked with their experiences of the nuclear accident. Some may recall it repeatedly in critical moments in life. I have actually encountered cases that the examination largely affected patients’ lives in unexpected ways.

I strongly feel that such system is really necessary to provide continuous cares matched to individual needs.

To protect “pride of Fukushima.”

From November 2012 to January 2013, the Ministry of the Environment, Japan implemented thyroid examination to a total of 4,365 men and women aged 3-18 years in three areas outside Fukushima Prefecture (Hirosaki City, Aomori Prefecture; Kofu City, Yamanashi Prefecture; and Nagasaki City, Nagasaki Prefecture) applying the same instrument and methods of in Fukushima Prefecture.

At that time Fukushima had been implementing the first-round of thyroid examination (even if there were radiation-induced thyroid cancers due to the accident, they would not have developed enough to be detected at the time of the first-round of thyroid examination). Therefore, a few people pointed out that we cannot conclude that “the thyroid cancer in Fukushima children is not attributed to radiation exposure” solely by comparing the “three prefectural surveys” and the first-round thyroid examination in Fukushima. However, the three prefectural surveys detected one thyroid cancer case (the same proportion with the first-round examination in Fukushima), and also revealed that the proportions of children who found cysts during the examination were similar between Fukushima and other areas. The results have gradually calmed down public anxiety and panic regarding the detection of cysts among residents.

Hayano: Even now, some people in various positions say, “thyroid examination should be conducted to children outside the prefecture in order to investigate whether thyroid cancer detected in Fukushima is attributed to radiation.” What do you think about this opinion?

Midorikawa: No. I strongly disagree with the opinion. Many people suggest implementing thyroid screening in other prefecture as well. They think that it is fine if participants’ consent is obtained or if we fully manage ethical aspects of the examination. Let’s say the screening outside Fukushima could prove that thyroid cancer in Fukushima is not attributed to the effects of radiation because it showed a similar thyroid cancer detection rate. However, would Fukushima residents be happy about it? Would Fukushima people be really happy to hear that “many thyroid cancers were also detected in other areas?”

Hayano: Ah, I am sure that they would not be happy at al.

Midorikawa: In my explanatory meetings with mothers, they often ask me “what results would be expected if the thyroid examination in Fukushima was conducted in other prefectures?” When I receive such question, I say, “thyroid cancer would be found in other prefectures as detected in Fukushima.” Some mothers say that “if that is the case, why not conduct the thyroid examination in other prefectures like Fukushima?” I understand very much how they feel and why they ask those questions.

If we conducted the same thyroid examination in other prefectures as in Fukushima, many thyroid cancers would be detected like in Fukushima, and many children would get surgery. Then, it would prove that “thyroid cancer found in Fukushima now is not specially increasing due to the effects of radiation.” If we, Fukushima residents, felt happy to hear such results and thought “that was good news,” Fukushima people would be hurt more deeply for a long time.

In my explanatory meetings, I say “we would lose our pride of Fukushima, if we became happy to hear such results.” Mothers then think deeply, and nod their head and say “you are right, Doctor, our pride of Fukushima would be lost.”

I was actively involved in the three prefectural surveys, and I did conduct thyroid examinations four times in Aomori. Also, in my explanatory meetings in Fukushima I explain the results from the examinations in the three prefectures. However, I regret very much that I conducted thyroid examinations in the three prefectural surveys. It is sad that unless we did such examinations, we could not inform the residents that “it is not necessary to worry about having a cyst.”

Residents’ anxiety created by the thyroid examination.

Currently, the full-scale thyroid examination is planned to be conducted to Fukushima residents who were 18 years old or younger at the accident and who were born within one year after the accident every two years until they reach 25, and afterwards every five years. Since the incidence of cancers including thyroid cancer increases with age regardless of the absence or presence of symptoms, the number of thyroid cancer cases is expected to increase if the thyroid examination program is extended to older residents in Fukushima.

South Korea conducted thyroid screening with breast cancer examination, and revealed that the detected number of thyroid cancer increased by approximately 15 times, whereas the mortality rate owing to thyroid cancer did not change (note 4). Based on this result, many experts claim the risk of overdiagnosis concerning that “if thyroid screening will also be conducted to people aged 30 and older in Fukushima, many cases that do not develop any symptoms (nor threaten human health) will be detected.”

(Note 4) Lee JH, Shin SW, Overdiagnosis and screening for thyroid cancer in Korea. Lancet 384(9957):1848, 2014

Ahn HS et al, Korea’s thyroid-cancer “epidemic”-screening and overdiagnosis. N Engl J Med 371(19):1765–1767, 2014

Vaccarella S et al, Thyroid-Cancer Epidemic? The increasing impact of overdiagnosis. N Engl J Med 375(7); 614-417, 2016

Lin J S et al, Screening for thyroid cancer updated evidence report and systematic review for the US preventive services task force. JAMA 317(18): 1888-1903, 2017

Hayano: Science cannot prove “there are zero effects of radiation in Fukushima.” However, various data including ones regarding initial exposure show that health effects owing to radiation exposure will be statistically negligible. I am not a specialist of thyroid. But, thyroid cancer detected in the thyroid examination in Fukushima after the accident is not caused by radiation exposure. This is already apparent.

Midorikawa: Many specialists both in and outside of Japan now believe so.

Hayano: Scientifically, it is well understood now that “the increase of thyroid cancer among children in Fukushima is not attributed to the effects of radiation.” This means that “this examination is detecting many thyroid cancer cases that would not be found in one’s lifetime in normal circumstances of not having such large-scale screening.” Furthermore, it is well known that many cancers increase with age. If the examination continues and expands to older residents, the detected number of thyroid cancer will, of course, increase.

Does it really help residents to detect many thyroid cancers that would not cause any symptoms till the end of their lives?

Midorikawa: I heard about cases that patients were almost treated differently from normal procedures at a medical facility outside Fukushima just because the person was in Fukushima at the time of the accident. As shown by this example, this examination can cause various harms to participants. I think that this examination should be re-evaluated through a full discussion in consideration of such harms.

If the discussion concludes that “this examination is not helping residents,” it would considerably hurt the feelings of many people who have ever participated in the examination and taken surgery. Therefore, even if we will discuss the future of the examination, it is very important to establish a system that can fully support people who are now and will be suffering.

Hayano: While many doctors, like you, are involved in the program and taking care of people carefully, there are still tensed scenes in press conferences of the Committee Meeting. Besides, TV and newspapers report “both-side arguments” about thyroid cancers detected among children in Fukushima. Some media spend the same amount of time or same size of spaces in papers to report “the views of many specialists or international organizations” and “the view of one researcher.” Because of such way of reporting, many people still think that a relationship between thyroid cancer and effects of radiation is unknown.

Furthermore, there are certain media that behave as if they wanted the examination would find thyroid cancers caused by the nuclear accident.

Midorikawa: When I see such media reports, I wonder if they want Fukushima to be such a dangerous place.

Hayano: When we analyze the trend of the frequency of word searching of “internal exposure” and “external exposure” based on the Google Trends, the frequency of searching “external exposure” have not been so large after the nuclear accident. The frequency of searching “internal exposure” is larger than that; however, it has been gradually decreasing after the nuclear disaster. Nevertheless, the frequency of searching “thyroid cancer” stays flat.

Additionally, there are sometimes remarkable spikes (in this case, temporal increases of the frequency of searching “thyroid cancer). These spikes occur when additional cases of thyroid cancers were reported. Furthermore, “thyroid cancer” has been searched mainly inside Fukushima Prefecture. These show that fear of thyroid cancer is not ever reduced although concerns of radiation have been reduced during six years after the nuclear accident.

Midorikawa: Thyroid examination itself, which is supposed to relieve concerns among residents and follow up their health, possibly causes new anxieties.

Hayano: At least, it can be said that “these data show such aspects.”

Benefits and harms of “the thyroid screening”

Most specialists inside and outside Japan have consensus that “thyroid cancers detected during the thyroid screening examinations in Fukushima are not caused by radiation exposure after the nuclear accident.” Generally, a screening has also benefits of early detection of diseases, such as cancers or lifestyle diseases that can advance without symptoms, and associated reduction in mortality rates.

On the other hand, screening has certain harms. Screening may detect false positives that can be only identified by advanced medical examinations. Another harm is over-diagnosis as found in this thyroid examination program in Fukushima: the screening detects many minor abnormalities that could not be found otherwise and would not kill people. Such harms result not only in unnecessary advanced examinations (including medical radiation exposure) and physical burdens owing to medical interventions, such as a surgery, but also in serious psychological burdens especially in children.

To relieve excessive concerns on thyroid cancer among residents and to enable children and their families to decide whether they participate in the examination or not, it is essential to explain the characteristics of thyroid cancer itself, as well as the benefits and harms of the screening examination. It is an urgent task for local and national media, such as television and newspapers, as well as central and local governments.

“Children in Fukushima are all right.”

After the above interview, I asked Dr. Midorikawa to provide us with a few words.

“Children in Fukushima are all right. I believe that children have potentials to thrive with what they have learned from this special experience.”

These is the massage from the doctor who has been engaged in the thyroid examination program and seeing children in Fukushima.